TL;DR: this is mostly a text version of a presentation I’ve done a couple times (English or Portuguese) on the history of building DigitalOcean’s API gateway. How we made it easier for folks to build new microservices instead of continuing to add code to our monoliths, the successes, failures and lessons learned.

First, where were we?

DigitalOcean had 3 monoliths back in 2016 when we started (all 3 are still alive today, albeit much smaller than they were before). Why were there 3? There is a shared library that contains most of the logic that all 3 applications use, so in reality we had one “monolith library” that was reused at all 3, most logic changes were made into this library and then it would be upgraded at every single app separately. The library still exists today and continues to be updated every once in a while.

As you can imagine, as more and more changes started to happen, with the company growing incredibly fast both in terms of business and hiring, this wasn’t ideal. Many times someone would change this core library, deploy one of the apps (the control pane you see when you sign in), but not the JSON API. So you could end up with a new feature visible at the control panel but not at the API. There would always be a time when this library version wouldn’t match across all applications, as we were not deploying them all at once every single time, so there was always space for there to be a mismatch of features available.

This also meant that the test suite was growing by leaps and bounds, getting slower, making running the test suite and deployments a pain. There was growing interest in doing something about this, but we couldn’t just migrate everything out. There was also a lot of interest in NOT doing Ruby anymore. There was a growing body of Golang code all over the place and people wanted to use it for their new services instead of building it all inside the old monoliths.

There was a catch here though, how could they possibly do all the things the Rails apps were doing, like authentication, rate limiting, authorization, feature flipping, routing, error handling and all the shared logic, in a new language, without repeating the same thing across all new projects?

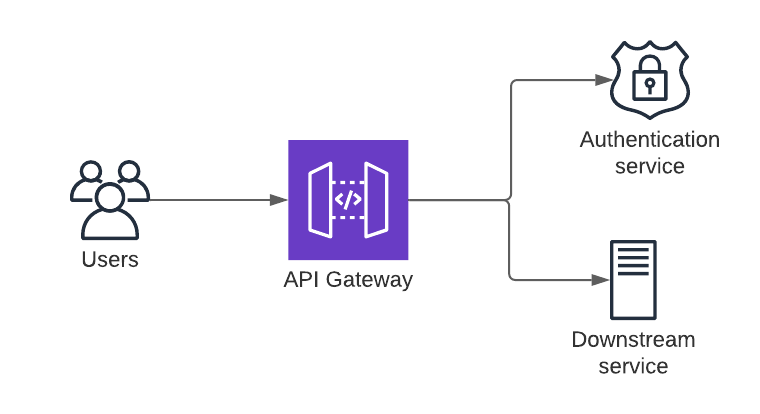

We needed something that would be language agnostic and could be run side by side with the existing monoliths. At this point we knew a library ( like Twitter’s Finagle) wasn’t an option. Our solution had to work with the old Ruby code and the new Golang stuff (and JS, maybe Python. It was all up in the air back then). We wouldn’t be able to build a library with all the shared features needed in multiple languages.This is where the API gateway comes in.

What is an API gateway?

The microservices.io patterns list has a great definition for the API gateway:

Implement an API gateway that is the single entry point for all clients. The API gateway handles requests in one of two ways. Some requests are simply proxied/routed to the appropriate service. It handles other requests by fanning out to multiple services.

It took us multiple meetings and discussions between Joonas Bergius, Nan Zhong, Joe Friedl, me and even Phil Calçado, who was the engineering lead (not sure if this was actually the title but he was the boss), to come to the realization that we were going to build an API gateway.

What came out of the brainstorms:

- It was going to be a pure HTTP proxy, no GRPC, GraphQL or other special protocols;

- We would not change request or response bodies, so there wouldn’t be any protocol translation. Applications would be responsible for parsing the input and producing valid outputs, in the format the client was expecting;

- We’d augment the requests and responses with extra information encoded as HTTP headers, including user information, rate limiting details, tracing metadata, features enabled, so all downstream applications would have to do was looking at the headers, not special exchange format.

- Route configuration would be self-service, teams would call a service with their route configuration and the proxy would automatically pick up changes and update it’s routing table. It would perform basic health checking and remove destinations that weren’t reachable, but otherwise would take any request and forward it to the registered services.

- It would also include filters that could be run before or after a request was processed, these filters would include authentication, rate limiting, feature flipping and all the other shared pieces teams would need to be available to build apps out of the monoliths.

Does it look a lot like Java’s Servlet API or Ruby’s Rack? Of course, those were the main inspirations for the design. Going for a simple, well known, design would make us move faster as there would be less stuff to do and we could always complicate it in the future. This was one of the best decisions we made and this is still the way it works nowadays.

Why didn’t we pick something that existed? Fair question. There really weren’t many options back then and the ones that did exist did not make it easy to integrate custom code. Our very first challenge was to decrypt and parse Rails sessions to authenticate users, and there was plenty of complex code to decrypt, unmarshal (from Ruby’s serialization format) and make sense of session data.

Nginx, that was one of the options when we started, only offered integration through Lua scripts, so we’d have to write this session decrypting and parsing logic in Lua scripts we’d bundle with our custom Nginx install and that did not feel like a great solution. It was hard to test the scripts, no one had any experience with Lua and the whole setup wasn’t robust, these scripts were seen mostly as doing small changes in the request flow, not for building complex logic.

So, we started building our own API gateway in Golang.

How did we start?

Once we had the basic proxy built, we placed it in front of some of the traffic, to make sure it could proxy correctly. The first two “filters” we built were the authentication filters, for Rails sessions and OAuth tokens. To roll these out, we started by “doing” the filter work for both monoliths but not acting on them, we’d check if the output we came to in our implementation was the same the monoliths decided on and if the response was also the same; if our own service said a request should be denied but the monoliths responded with an OK or the other way around, we’d log that and work on figuring out why it didn’t work.

As we built these filters, another pattern emerged, instead of having all this code inside the API gateway itself, we thought it would be faster to separate the code into a separate service. The initial goal was mostly to make it reusable by other teams if needed and make it easier for us to deploy smaller changes as deploying the gateway itself was a complicated and slow process (due to the way our internal K8s clusters networking was setup back then, we couldn’t run the gateway on them, so it ran on droplets). After that, almost all filters were just glue code to call an external service that actually knew how to get the job done.

While it was a response to environmental constraints and not really something we planned, this design made the gateway itself smaller and more reliable. A lot of the logic would live in these microservices instead of the gateway and updates to them had a much smaller blast radius when something went awry.

@nanzhong finally switched it to serve all traffic sometime in November 2016, a couple months after our announcement, including full support for authentication with the Rails session and OAuth tokens.

Onboarding the first customers

So far we had only done work internally. We weren’t exposing any of this to other teams yet, as we wanted to verify it was all behaving as expected before letting people register their services. The first integrations were bumpy and the experience for the teams we were integrating with was hard.

We lacked documentation and good examples. Teams had to come to us frequently to make sure their services were really up, their configurations were valid, how routing would work (what options are available? Can I use wildcards? Can I use URL parameters? In what order are routes matched?) and how they should integrate route registration into their workflows. This led to a lot of manual labor on our end helping people do stuff they could be doing themselves had we done the work to make it easier to onboard them. The lesson here was clear, if you’re working on infrastructure, make sure you can stay out of the way when people are doing their work, you want them to work on their time and not be an impediment for their work.

We also lacked best practices for what the backend services should look like. Multiple teams were being formed of new developers that didn’t have a lot of experience with building applications with Golang and we did not provide guidance here on how they should set up their applications and what configurations were important.

One recurrent issue we had at the beginning was that Golang’s http.Server class assumes all timeouts are infinite unless you set them (ReadTimeout, ReadHeaderTimeout, WriteTimeout, WriteIdleTimeout) and this would lead to services getting a broken connection from the client (the API gateway) and wouldn’t know what it was until we checked their configs and noticed they just didn’t set a value (while we did have a max timeout for all requests on our end, so we’d close a connection that took too long).

Providing better guidance here for basic options and configurations that teams should be doing in all their apps would have saved a lot of time and effort for everyone.

Next, when registering routes, teams would talk directly to the key-value store we were using to store the routing table (Consul) and as you can imagine this wasn’t ideal. There was very little validation in place and it was super simple for people to register routes that wouldn’t load or that wouldn’t really route anything due to being incomplete. This eventually led to an outage where there was a nil in a place where the gateway did not expect a nil to be that would crash it whenever it loaded routes., Not a good day, I must tell you.

A new service then emerges (microservices all the way) to be the route collector. It would be the bridge between clients and the gateway, validating routes before sending them to Consul and producing a single list of routes with all services the gateway could use to build its routing table. The gateway would poll this service to get the current routing table whenever it changes and update itself if needed, it would still have a local static routing table if the routing service was not available when it started to at least some known destinations. @sivillo led the charge building this one.

Here’s how a service config looks like:

service := &config.Service{

Name: "uuidaggregator",

Routes: []*config.Route{

{

Hosts: []string{"uuid-generator-api.digitalocean.com"},

Paths: []string{“/generate-uuid”},

BeforeFilters: []string{

edgeconsts.FilterOauthTokenAuthentication,

edgeconsts.FilterEnsureAuthentication,

edgeconsts.FilterPublicAPIRateLimiter,

},

},

{

Hosts: []string{“cloud.do.com”},

Paths: []string{“/generate-uuid”},

// perform cookie session authentication for cloud requests,

// if it fails deny the request using the ensure auth filter

BeforeFilters: []string{

edgeconsts.FilterCookieSessionAuthentication,

edgeconsts.FilterEnsureAuthentication,

},

},

},

// Timeout in seconds for the entire request (Default 10s; Max 60s)

Timeout: 15,

MaxIdleConns: 5,

Destinations: []*config.Destination{

{

Scheme: "https",

Host: fmt.Sprintf("uuidaggregator-tls.com"),

},

},

// this health check config is optional, the defaults are ok

HealthCheck: &config.HealthCheck{

Path: "/health",

IntervalInSeconds: 5,

MaxFailedAttempts: 3,

MinSuccessfulAttempts: 3,

TimeoutInSeconds: 3,

},

}

When building the routing table, as it’s not made of a single routing file as you’d see in a Rails application, we also had to do some work. We couldn’t just register the routes in the order the services showed up as almost all routers will stop at the first match. That means that a route like:

/api/v1/droplets/*

Could possibly come before something like:

/api/v1/droplets/*/actions

And that would cause the first one to be matched and the second one to be ignored just because of the order they were registered, especially if they were registered in separate services. Our solution here was to first prefer routes that had a domain and/or methods defined and then sort them by longest path, so longest routes, that would effectively produce the longest match, would be found first. We also push full paths before wildcard routes, so the routing table first tries to match the full path matches and only then goes for the wildcard routes that still follow the same pattern of longest matches first, preventing the problem above.

Also, if I were to start this all over, we would not support wildcards for routes at all, in an API gateway almost all times the services know the paths they support already so here’s no need to have this complication on your routes. Just match it all on exact matches and avoid the wildcard nightmare. In a distributed environment with dozens of services like we have today, they make the routing table hard to reason about and don’t really bring any benefits other than making developers type a bit less.

The single entry point for everything

Being the single entry point for all requests that deal with account resources and the accounts themselves, we were in a position to collect data about every single service we had behind us and offer that to the teams that were registering their services. This made the API gateway an important piece when detecting and working through incidents as it had a general view of all services but it also made us a pretty common target for when stuff wasn’t behaving as expected.

Whenever something broke, we’d be the first or one of the first teams to be engaged as we were the entrypoint for everything and we had a better understanding of what was going on. That, obviously, wasn’t ideal but was also another side effect of not thinking about how people out of the team could consume the information we were collecting. We had our own dashboards with metrics and visualizations but they were not easy to understand if you didn’t have all the application and metrics context. It had no explanation for the metrics, thresholds or hints as to what was going on.

Thankfully, our Observability team did actually know how to build dashboards and we shamelessly copied their style building dashboards for our operations team with plenty of explanations, simpler components with coloring schemes that made it easy to check if something wasn’t behaving as expected, and hints. This way they could quickly figure out where an outage was going on, what systems were being affected and how, without having to engage us on every incident.

This also led us to eventually build general dashboards with all metrics we collected for every single service we had registered, automatic alerts for when services were misbehaving (too many 5xx, failures to produce responses, failure to health check), logging trails for all requests that were served, even if the backend service had crashed, so teams could quickly debug what happened on their end even if there were no logs or data on their own metrics or logs.

Adding security measures was also simplified, as our security team would just request or build functionality that made all services more secure by default, introducing filters in all requests to perform basic sanitization and checking. Services didn’t even have to add this to their configs, we’d just introduce them on all routes by default and they’d be none the wiser.

Building features

While we were mostly building new code it was to support or cover existing Ruby libraries or APIs and we had to make it all work seamlessly both for the new apps and for the existing Ruby ones. This led to many implementations that had to either behave the same way or had to expose APIs compatible with what the Ruby apps were doing, otherwise we could end up with a problem where the new microservices and the Ruby app wouldn’t agree with each other.

One of the first examples of this was when @lxfontes was doing our rate limiter. The original solution was based on rack-attack and backed by Redis, as it was shared across the whole API we couldn’t really build something completely new as it would lead to the microservices getting a rate limit that was different than the one you’d see if your call went to the old Ruby API app, the new limiter had to work the same way the Ruby one did so they would both produce the same response. This was both good and bad, as the basic idea of how rate limiting would work was already implemented and we could just read the code in Ruby and port it to Golang but it also made it harder for us to improve upon the solution with a new or better implementation as it would lead to conflicting rate limiting values being returned to clients.

Another case was the feature flipper. We were using jnunemaker/flipper to perform feature flipping but was getting slow for the amount of users we were flipping and we also had to expose it somehow for the new applications. This time we could actually build a completely new service because the library had support for an HTTP API backend, so we built a new, faster, backend and implemented the HTTP API the library expected, so the Ruby apps could continue to call this HTTP API to perform feature flipping while other services connected to the GRPC service that was now the main interface to flip users.

We even had to expose some of the Ruby code, mostly authorization policies, as a GRPC service so people wouldn’t have to rewrite all the policies they already had in place themselves. We just stood up our shared ruby library as a GRPC service and had services call it to run the policies they needed to authorize users. While this wasn’t something that was directly connected to the API gateway work it was still part of our mission to make all the shared infrastructure that was part of the monoliths available for the new microservices that were being built and I think this is a dead simple way to kickstart your move out your existing monolith.

We tried as much as possible not doing big bang migrations and rebuilding everything from scratch with incompatible interfaces. There was no time to migrate everything, including the old Ruby code, so the new implementations always had to maintain some compatibility and this made migrating into the new services much simpler and mostly invisible for people that were using the legacy systems.

Still kicking

As I write this the Edge Gateway, as we call it, is still there serving every single request DigitalOcean’s API and control panel take and some pieces of it seem to have had a bigger impact in what I think is our success so far.

Not being a library

Teams don’t talk to the gateway itself, it’s a somewhat invisible piece of the puzzle for anyone that’s not on our Edge team and this has made our life so much easier. There is no direct dependency between the apps we proxy to and the gateway, they all agree on a set of HTTP headers that will contain extra information and that’s it.

When doing integration testing for the apps, you can send these headers to yourself as if you were the gateway (in production services use mTLS to verify they are indeed getting a request from the gateway) and this relieves us to ask people to upgrade libraries when we add features or update existing functionality. It’s just HTTP, no magic at all.

Being self service

It took us some time to sort out all the kinks and make it easier for people to register their services, but from the get go we decided we did not want to be involved in the way people register their services. This might have led to some more work initially on our end to find the possible ways the configuration could be invalid (and we still find cases every once in a while, like adding a filter that expects the user to be authenticated but not having any authentication filter before it in the route) and prevent taking over routes but has led to teams being able to get their services registered much faster and without having to ask us for “permission” on pull requests.

If you’re working on an infrastructure team, you should do all in your power to avoid being the “gatekeeper” for the teams you service. Also, people often don’t think about User Experience when building infrastructure services and that is a huge mistake, infrastructure services still have user interfaces and you have to think about how you’re going to expose that for users, including providing sane defaults (real timeouts instead of the infinite timeouts in Golang’s default HTTP client and server) and blocking operations that might be syntactically but not logically correct.

Being reliable

Monitors, smoke tests, integration tests, constant verification through internal and external callers that the service is doing what it’s supposed to do. We knew from the get go that getting people to trust us, the new team, building a new application that could eventually become a single point of failure for the control panel and API, would get a lot of effort and would be really hard to maintain if we made too many mistakes causing downtime. Being reliable paid off, even if we did cause incidents here and there :D

Don’t impose

Still today, you can add features to the old monoliths, they’re still there, taking a fraction of the traffic they used to when we started, but they still exist and that’s a good thing. While we wanted to turn them off we knew this wasn’t going to be the end goal, the end goal for us was to make our platform so much better that people wouldn’t even think about building stuff on the monoliths. We offer more features, metrics, dashboards, better error handling, logs and more.

Had there been a mandate for people to “use the Edge gateway” people would feel forced into using us even if it wasn’t the best solution. Internal teams should assume people using them are also customers, because they are, and offer a solution that solves a need they have. A relationship that is forced upon the other team will eventually lead to workarounds and bad outcomes.

The team

We wouldn’t have arrived where we are right now without the multiple people that had a hand directly or indirectly here, Julian Miller that has been on the team for as long as I remember by now and has had his hands in everything we’ve done, Nan Zhong, Louis Sivillo that was also on the team for a long while and led the charge in building our route collection service, migrating routes from the old storage and making sure it was all seamless for the folks using it, Lucas Fontes and Joe Friedl that made important contributions building features people still depend on every day when they were on the team, Dave Worth, Mike Holly and Hugo Corbucci, that had much more context on everything DigitalOcean and were always there to answer questions when I had no idea where something was or how it worked, Joonas Bergius, the first Engineering Manager on the team that was there building the architecture, validating ideas and getting us to deliver on the goal of improving the experience for teams building microservices at DigitalOcean, Steven Black, our second EM, that made sure there was a place for the team to grow and continue to build new features and Nick Silkey, our current EM, master of getting stuff that’s important done and finding budget where there wouldn’t be any. It took many hands to get us to where we are now and many more to keep moving it forward.